The meeting went badly. Very badly.

The CMO was thirty minutes early, and the CEO was twenty minutes late. The COO and CMO were both attempting to lead the meeting, while simultaneously offending each other for doing so. Meanwhile, the CFO and CIO interrupted them constantly, both steering the conversation where they saw fit. After two hours of this, when it was time to make decisions, the CIO was only concerned with the short-term, cost-effective approach, while the CMO was focused on the long term results. In the end, no decisions were made because the CEO and CFO refused to move forward without a complete consensus from the team.

No one anticipated that the first global leadership meeting would be such a mess. Yet it turns out that the leaders could have been better prepared for the meeting. How? All it takes is a little cultural awareness.

When I say cultural awareness, I don’t mean to imply that all you need to do is be aware that cultural differences exist. Cultural awareness comes from learning about other cultures, with a sincere effort to understand them. On a personal level, you can ask members of other cultures about their geography, music, history, and/or literature.

On a theoretical level, you can turn to Geert Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory, as a framework for building a greater understanding between different cultures in an organization. Social psychologist Geert Hofstede conducted a six-year worldwide survey of employee values in 50 countries and three regions, identifying cultural differences in six primary dimensions. These dimensions address four anthropological problem areas that national societies handle differently.

While the six dimensions may seem a bit abstract, they inform important aspects of business relationships, including how people view hierarchy, time and decision making. These three elements cause conflict in the workplace even when there are no cultural differences. Toss a group of people into a room who are not culturally aware, and you get bad meetings.

Since hierarchy, time and decision making are so often the cause of workplace miscommunication, a client of mine asked me to discuss the different cultural perspectives of each. Because the client has global offices in Sweden, India, China, the United States, and the United Kingdom, I will focus exclusively on those countries.

Keep in mind that this is a basic overview, which involves generalizations. Ultimately, everyone you work with is an individual who will have his or her own perspective.

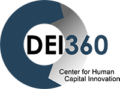

Cultural Differences With Time

Let’s start with time. There are early people and there are late people, right?

It’s not that simple. Different cultures have different perspectives of time on a fundamental level. Here is an overview of how the UK, U.S., China, India, and Sweden generally approach the concept of time in business.

U.K.: In the U.K. it is customary to be punctual. Meetings are generally time-consuming and set well in advance. Agendas are preferred.

U.S.: In the U.S., time is seen as a precious and scarce commodity (think about the phrase ‘time is money’). Culturally, people in the U.S. tend to equate working time with success—the harder you work (more hours), the more successful you will be. They see time as linear and doing one thing at a time with a fixed schedule is preferred.

China: China is a big proponent of punctuality. In fact, it is customary to arrive 15 to 30 minutes early to a meeting in the Chinese culture. Other people’s time is seen as precious, due to a penchant for humility. It’s wise to allow time in a meeting after a transaction is decided to attain a degree of closeness. In other words, don’t shake hands on the deal and run out the door to another appointment.

India: The Indian perception of time is not linear. Time is not about countable, segmented hours and minutes, but rather is measured in events, priorities, and emergency requests. Expressions of time are expressions of intent, not mathematical.

Sweden: In Sweden, being punctual is a sign of respect and efficiency. It is also not considered rude to set strict deadlines for projects or decisions.

What’s Time Got To Do With a Bad Meeting?

So let’s go back to the horrible meeting we talked about earlier. Remember how the CMO was thirty minutes early, and the CEO was twenty minutes late? The early leader wasn’t anxious or trying to show people up by being early; she was just from a culture where early arrival is customary. And the CEO is from a different culture—one where expressions of time are expressions of intent, not mathematical. If the whole team was aware of these cultural differences, the meeting wouldn’t have started with tension.

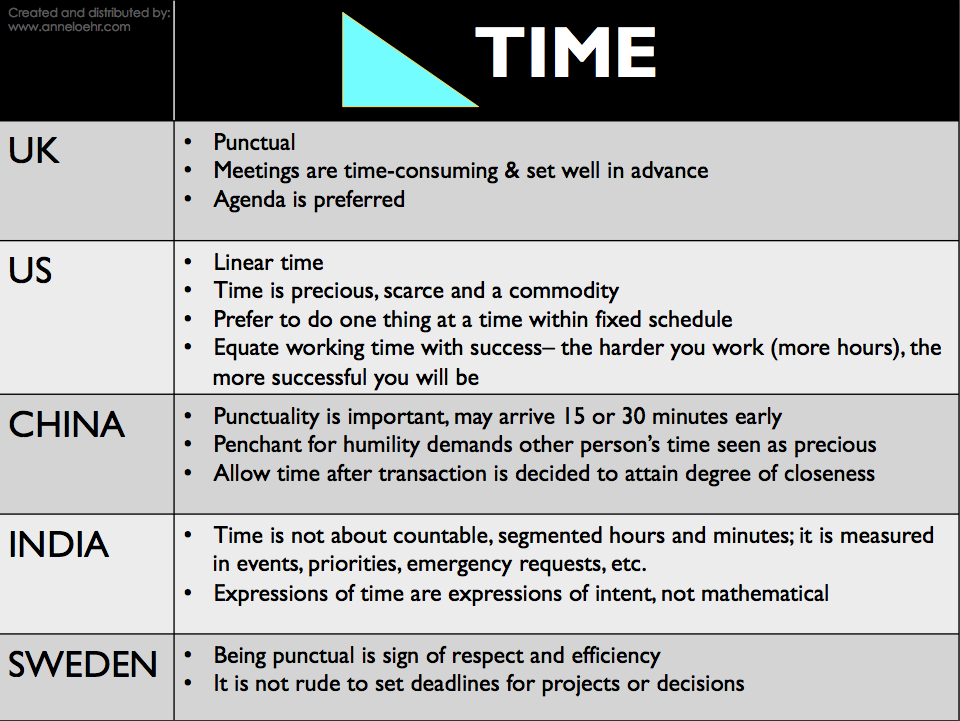

Cultural Differences With Hierarchy

Now let’s move on to hierarchy. The concept of hierarchy, a system or organization in which people or groups are ranked one above the other according to status or authority, varies widely among cultures. While some cultures find hierarchy to be a must, other find it intrusive and unnecessary. Here is an overview of how the UK, U.S., China, India, and Sweden generally approach the concept of hierarchy in business.

U.K.: Distinct hierarchy characterizes the majority of British organizations and organizations. The decision maker’s authority is not to be questioned, and major decisions are made at the very top. Culturally in the U.K., the people consider a group-established order to offer a sense of security and something with which they can identify.

U.S.: The US often has a hierarchal corporate structure, where there is top-down control that guides business practices and activities, and positions are ranked with levels of authority. However, the U.S. is culturally uncomfortable with hierarchy and class systems. They prefer the “open door policy” and using first names, or even nicknames, with superiors.

China: In China, hierarchy influences many aspects of business. Seating arrangements require the most influential people seated the farthest from the door, and top ranking dignitaries face the door. A person in a subordinate position would never speak for the group, and senior managers do not expect or appreciate being contacted by more junior people from outside organizations.

India: Indian businesses are often very hierarchal. In negotiations, unless members of the highest level (organization director, owner, senior manager) are present, a decision will not be made. Roles are well defined and once people are in their allotted position, they rarely attempt to overturn. Leaders are respected and their instructions are unlikely to be questioned—even raising a red flag can be seen as disrespectful.

Sweden: In Sweden, strict hierarchy is largely absent. Everyone’s role in the group is seen as important and managers invite feedback from all team members. In general, many angles are discussed before a group-wide decision is made.

What’s Hierarchy Got To Do With a Bad Meeting?

Remember, “The COO and CMO were both attempting to lead the meaning, while simultaneously offending each other for doing so. Meanwhile, the CFO and CIO interrupted them constantly, steering the conversation where they saw fit.”? Can you guess where these leaders might be from? The COO and CMO are both from cultures where hierarchy is an important and respected structure, like the UK and China, and the CFO and CIO are from cultures that shy away from hierarchy for a more casual, collaborative approach, like Sweden or the United States. Had these leaders been more culturally aware, they would have seen what was happening in the situation and been able to adjust their behavior accordingly.

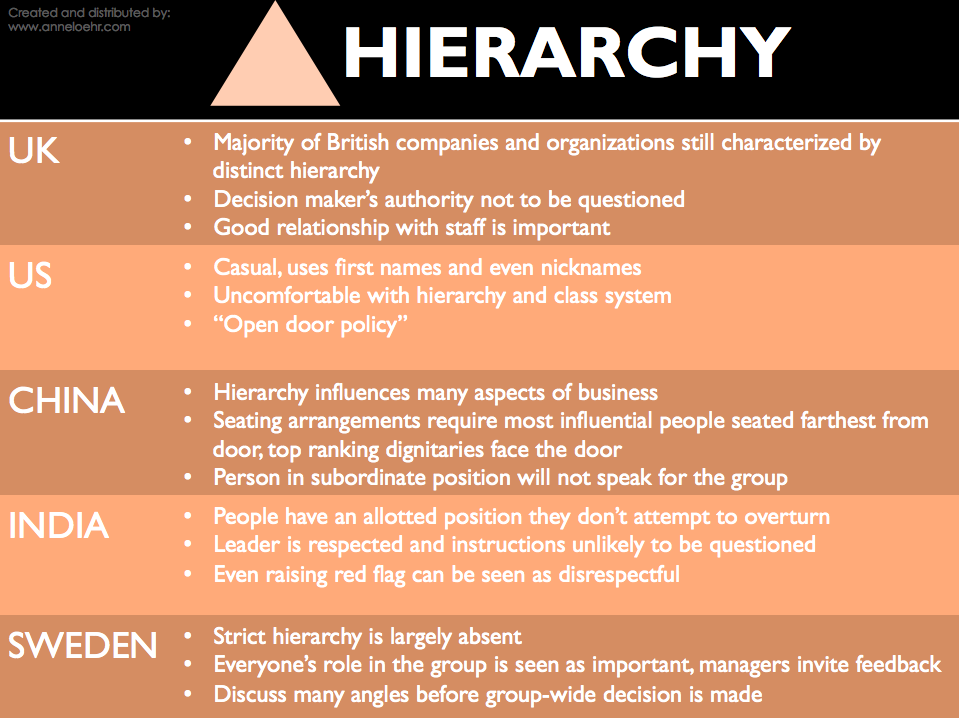

Cultural Differences With Decision Making

Cultural differences in decision making is the last topic we will cover today. This isn’t about being indecisive or not; it’s about how decisions are customarily made. Not understanding how this process differs among cultures can not only create frustration, but also prevent decisions from happening at all, which hampers progress. Here is an overview of how the UK, U.S., China, India, and Sweden generally approach the concept of decision making in business.

U.K: When a decision is announced, it might sound more like a proposal open to discussion yet that is not the case in the U.K. They favor a pragmatic approach to decision making and use logical reasoning.

U.S.: In the U.S., executives are influenced by a short-term, cost-benefit approach to decision making. They approach decisions in a democratic fashion, operating on debate and discussion between opposing parties. Decisions are made either to respond to challenges or create opportunities for recognition and praise.

China: When it comes to China, decision making tends to be authoritative, which employees rarely challenge. They trend toward decisions based on long-term goals, instead of short-term goals.

India: All attendants of a meeting need to be considered in the decision making process in order to maintain harmony in India. This can create a longer decision-making process, often considered by other cultures as time consuming. They tend to value stability when making decisions.

Sweden: Compromising is strongly favored in Sweden. Getting into a heated debate in a typical Swedish meeting would be unusual. Decisions are made with great consideration because they value consensus and agreement and feel it cannot be risked.

What’s Decision Making Got To Do With a Bad Meeting?

Let’s go back to that horrible meeting one last time. Remember the CIO and CMO clashing when it was time to make a decision? The CIO was most concerned with a short-term, cost-effective approach, as is common in the U.S. culture. This conflicted with the CMO who was focused on the long-term results. And in the end, the CEO and CFO were so concerned with all team members being involved and invested in the decision, often culturally relevant in India and Sweden, that a decision was never made.

Armed with this basic knowledge of cultural differences in time, hierarchy and decision-making, the horrible meeting could have had an entirely different outcome.

I challenge you to look more into cultural differences as you approach your professional life. One way to do that is to look more into the Hofstede Cultural Dimensions Theory. Another way is to nourish your curiosity, ask questions, and really listen to what your team members have to say. This will improve your effectiveness, improve your work relationships, and enrich your life.

I would love to hear any stories you have about misunderstandings at work in regard to hierarchy, time or decision making style. Were you able to see what was happening at the time? Are you able to see it more clearly now?

Leave a comment below, send us an email, or find us on Twitter.